I’ve been thinking about the Jewish perspective on death. My dear Amy who died on February 9th, and will be memorialized this Sunday in Portland, dug back into her Jewish roots during the pandemic and continued a study of Hebrew and a weekly celebration of Shabbat until the end. Her husband even converted, and they took their Jewish spirituality seriously these past few years. It was a sense of spiritual connection they sought, and finding a community at synagogue helped them through the last few years of Amy’s recurrent breast cancer. At Amy’s burial it was apparent how important having a rabbi and Jewish community was to help the transition from life to death.

Though my name is deceiving, I come from Orthodox Jew and Zionist roots on my mother’s side. My mother married a goy (McElroy) in 1961 and rejected her Jewish heritage, but it was deeply ingrained in her despite her best efforts to shed it and free herself from what she saw as religious shackles. When we would spend summers in London with my grandparents when I was a child, and Amy came along on more than one occasion, Shabbat didn’t feel celebratory. It felt heavy and compulsory and bristling with feelings and words unexpressed. But I remember it. I remember how the prayers and food had a sadness and solemnity about them, how my grandparents (and my mother) had lived through World War II, how they had lost siblings on both sides of their families in Poland, and the fact that they were Jewish and alive was important. I recenly located a letter the writer Stefan Zweig wrote to my grandfather Lefty in 1940, which expressed the pain the war was causing them.

I asked myself this week if Jews believe in an afterlife, really trying to make sense of whether Amy possibly had come around to believing in one in her final days, and I came upon the term “olam ha-bah” which translates as “the world to come.” It stands in contrast to “olam ha-zeh,” this world. Now is not the time for me to become a Jewish scholar. I think my grandfather Joseph Leftwich can retain that title in my family tree. But I like to think that olam ha-bah for Amy represented an end to her strife and pain, that it provided some kind of solace for her husband, who was such a solid and steadfast partner for her the last fifteen years. Amy joked that she was a Jewish atheist, and that makes perfect sense. She was much more concerned with living a kind and generous life on this earth than worrying about what comes after.

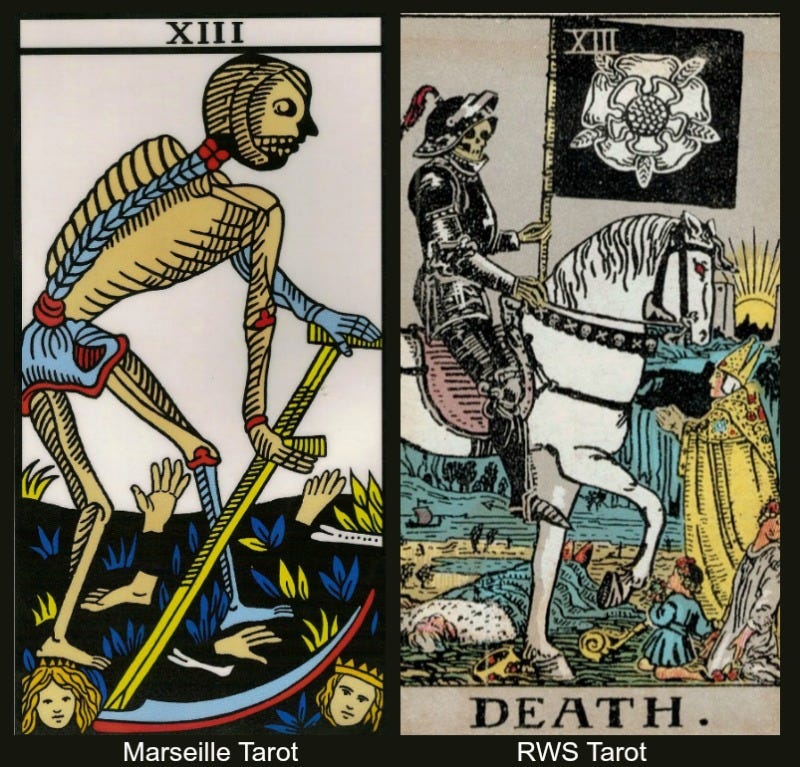

In modern day tarot when we talk about Death we don’t take the card literally. I think this is pretty universal among readers and writers about the tarot, although I imagine it was in fact taken quite literally during the Renaissance. Death comes to us as transformation and change, as the need to put something down so something else can be picked up. Death can be painful but also has a beauty to it in the idea that life is process and death is process and process is process, all movement. And yes, sometimes that process might be a physical death. But more often it is a change in perspective, a spiritual death, a need to release that which does not serve us.

Amy’s year ahead spread for 2024 only made it two months but those two months were telling. The Five of Swords for Janaury and the Ace of Swords for February. I like to think that the olam ha-zeh was some kind of final battle, so that she could have peace and a fresh start in whatever the olam hab-ah is. Death shows us the world to come, Amy. And that world to come for me is a world without you in it.

xo Hanna

**the title of this post is from The Doors, “The End”